Research for the Church Scientific workshops led me to produce a series of diagrams to illustrate some ideas from the Reformational philosophy tradition that inspired this project. Most of these were originally published online at the Faith-in-Scholarship blog, but they are reproduced here in a more instructive order and with edited descriptions. Clicking on an image will, in most cases, take you to the original blog post.

This page offers a summary of Reformational thinking about theology and philosophy of the natural sciences. There are some references for further reading – or for a more visual tour, try the animated Prezi of the workshops programme.

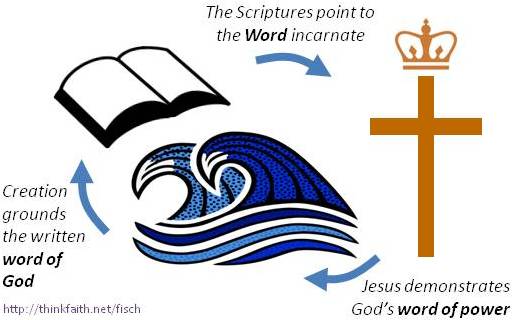

The Word of God and Laws of Nature

As used in the Bible, “word of God” has three important senses. There is the word of God as Scripture itself, the Word made flesh in Jesus Christ, and the word of God that commands and upholds the created order. That last sense is crucial, yet often overlooked [1]. From the first “Let there be light!” to the indication in Hebrews 1:3 that the Son of God “upholds all things by the word of His power,” the Scriptures contain many references to God’s word as agent of natural processes (e.g. Ps 147:15-20), and there are important analogies between God’s word and God’s law (e.g. Ps 19).

What is science?

So we can propose a simple working definition of scientific research as “the search for God’s word as it structures the created order.” That is to say that scientific work aims at articulating structural universals in the cosmos that emanate from God’s word of power. The natural sciences focus on laws of nature, structures and functions, classifications and principles; if we look as far as the German concept of Wissenschaften (‘science’ as scholarship in general), we can also point to the identities and theorems of mathematics in one direction, and to the typologies, theories and frameworks of the humanities (even theology) in the other.

Next we look at the relationships among science, philosophy and religion. But before thinking about science, we should remember that, starting from Christ and guided by the Holy Spirit, we can know God through His word in all its three senses, before engaging in any scholarship. Scientific, philosophical and theological study are important callings that we may pursue in faithfulness to God and His kingdom, rather than ways to know God.

[1] Probably the best introduction to this theme is Gordon Spykman’s Reformational Theology: A New Paradigm for Doing Dogmatics (1992, Eerdmans).

Science, Philosophy and Religion

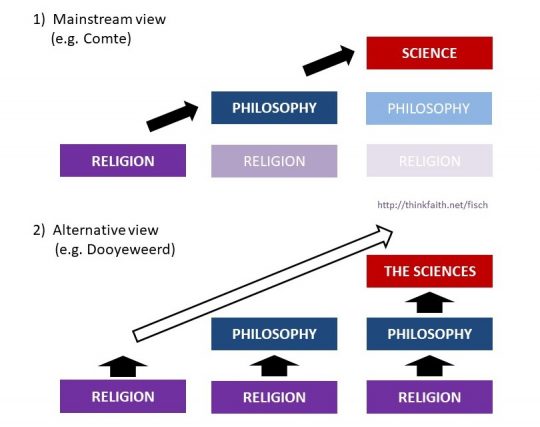

Where does science come from? Historically, the predecessor of what we now call the sciences was natural philosophy, which was, evidently enough, a branch of philosophy. But when we study science at school and university, it’s rare to hear much mention of any continuing dependence on philosophy. We seem to study lots of scientific “facts”: about the universe, the solar system and the earth, about impacts and reactions, about microbes, plants and animals, and about humans and society. We gradually get introduced to experimental methods as ways of testing hypotheses and perhaps to demonstrate the tentative nature of scientific conclusions (after all, school science experiments rarely give textbook outcomes!). Eventually we’re told about scientific models and sometimes even about some controversies. Some of the “facts” are confusingly known as theories. But philosophy? That seems to be just a sideshow – at best a defunct predecessor.

There is another view, where all of the content of science curricula is dependent on philosophy. Learning about underlying laws, patterns and structures in the cosmos on the basis of specific data is fundamentally a philosophical problem, raising questions about what these underlying universals might be like and how our specific perceptions can relate to them. Then there are also questions of error, fallibility, bias and so on. Philosophy should not be merely of historical interest for scientists! And Christians should be interested in this view, because of where philosophy comes from.

Philosophy

Where does philosophy come from? Historically, one answer is that the Western philosophical tradition arose in ancient Greece as a competitor to the prevailing pagan religion. Now, in some philosophy courses there’s even less discussion of religion than there is of philosophy in science courses. But once again, there’s a hidden dependence. Philosophical arguments may invoke concepts like substance, abstract objects, minds, reason, justification, freedom and so on. And many of these turn out to encapsulate clear or hidden notions of how reality is constituted and where it comes from, what a human being is, what persons are, and so on. So religion should not be merely of historical interest in philosophy. In fact there is the possibility of building a Christian philosophy, for example, on the basis of a biblical worldview.

The diagram above, conceived by Richard Russell, illustrates two views of the relationships among these areas of thought. First is the Enlightenment view, in which religion is superseded over time by philosophy, which is in turn superseded by science. Below that is a view that’s characteristic of streams of Reformed thinking like the Reformational philosophy pioneered by Herman Dooyeweerd. The first option makes the challenge of being a scientist look simpler and less susceptible to controversy. But the second one is arguably far more realistic. We look more at how this ongoing dependence works below.

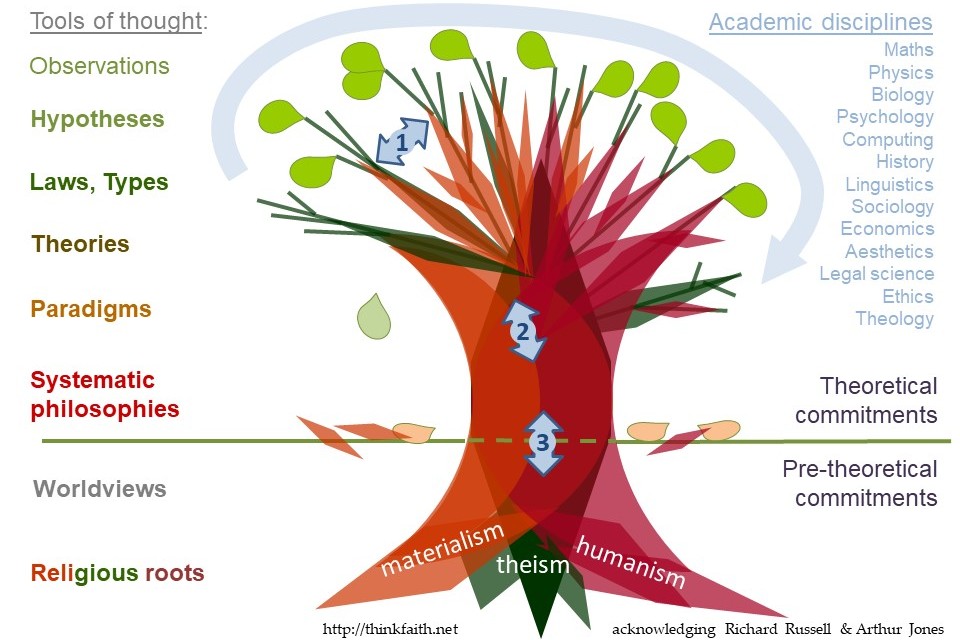

The Bush of Knowledge

Above we sketched a general connection between religion and the sciences, via philosophy. The ‘bush’ model illustrated here presents a more detailed view of this relationship. Whereas it is often claimed that the scientific disciplines are now autonomous (1) with respect to each other, (2) with respect to philosophy and (3) with respect to religion, a historically and philosophically aware scientist will realise that these three autonomies – especially (2) and (3) – are impossible in principle. A Christian re-formation of philosophy and all academic disciplines is then possible; indeed, it is necessary: for it is mandated by the First Commandment: to love God with our minds [1], and so to make every thought subject to the lordship of Christ [2].

Scientific hypotheses have deep roots

The diagram here illustrates, for the sake of argument, three religious roots that have intertwined in the development of academic disciplines. Theism, materialism and humanism underpin a range of worldviews (pre-theoretical, non-scientific commitments) that have motivated academic work. They in turn produce systematic philosophies that spawn analytical research in communities gathered into a range of disciplines. Paradigms (in Thomas Kuhn’s sense) are generated in each discipline, and working within these, academics hold to theories that contain laws, structures and typologies. These in turn lead to hypotheses, which may in time become new laws and so on. Any of these elements may also in time be discarded – but generally not on the occurrence of a single refutation: even hypotheses are theoretical commitments! (Dick Stafleu has explored this paradox [3].) At the tips of the twigs here, we have observations represented as leaves. These have a different status from the other ‘tools of thought’ because they are unique particular experiences. Data are not so much part of scientific knowledge but guide our discernment of the underlying structure of reality, represented by the rest of the bush.

Finally, this model makes clear that there is no simple deductive relationship between religion and the contents of the academic disciplines. What is proposed is a hierarchy, with the lower levels providing the conditions for the possibility of the higher ones: their transcendental pre-conditions. What should also be clear is that the development of Christian philosophy is a prerequisite for a serious Christian renewal of the disciplines (what Dooyeweerd calls the special sciences), for otherwise they will remain in the grip of non-Christian philosophies and religions. Without Christian philosophy there cannot even be a Christian academic theology that is faithful to the biblical religion.

[1] Matthew 22:37

[2] 2 Corinthians 10:5

[3] See MD Stafleu (2016), Theory and Experiment, section 10.1

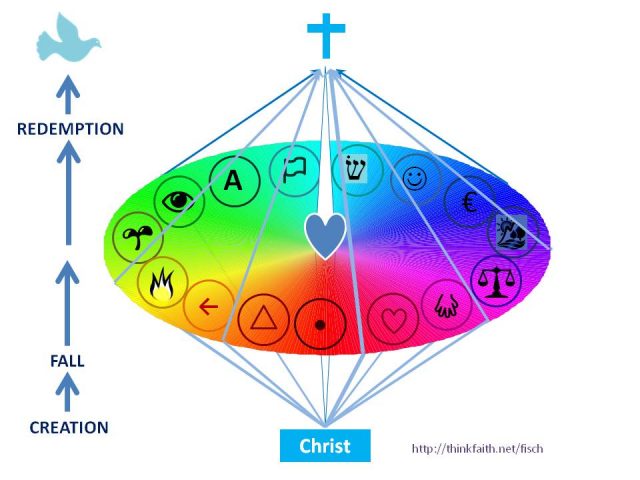

The Transcendental Context

This graphic represents the whole created world as having both immanent (horizontal) and transcendent (vertical) dimensions. It looks a bit like one of those spinning colour wheels you can make by pushing a pencil through a disc, and indeed that’s not a bad model for this big idea of what the world is like. The horizontal disc represents the whole universe of our day-to-day experience, with all the rich, scintillating diversity of temporal things and relationships that we know. This is the reality that everyone experiences in ways we can broadly agree upon: human society and institutions, people, animals, plants and inanimate things, all functioning in many different ways (represented by the 15 symbols around the circumference). At the centre of the disc lies a heart symbol, because this is a model of how we humans experience and influence the cosmos as we look out on it. That much describes the immanent dimension of reality.

Out of the heart

The human heart is also at the central point in this disc because the Bible reveals that humans are created as the image of God: the creatures that should image God to the rest of the creation (Genesis 1), and with whose obedience or disobedience the fate of the whole creation is tied up (Genesis 3; Romans 8:19). And Scripture uses ‘heart’ as a metaphor for our religious centre: the concentration point of our conscience and our will, which directs our worship either to God or after an idol. Here, of course, we’re moving beyond immanence perceptions to revealed truth about transcendent reality – which is represented by the vertical dimension of the diagram. This dimension represents what might be called cosmic time or a religious metanarrative: the all-embracing story of the cosmos from creation by God through the Fall in Adam to redemption in Christ Jesus, led by God’s life-giving Spirit. This is a bigger view of time than merely clock time, stretching from the primordial creation, the religious origin in Christ, to creation’s eternal destination, which is for Christ (think of Colossians 1:16). And our heart in a religious sense participates in this ‘depth dimension’ of the cosmos: we transcend our own lifespan by yearning to participate in God’s eternal purposes and to be granted eternal life at the Resurrection (as Paul does in Philippians 3:11).

How to avoid scientific idolatry

This diagram is based on the Christian philosopher Herman Dooyeweerd’s model of reality. Every philosophical view presupposes some religious notion of reality, typically including an idea of where reality comes from (its origin), what holds it together (its coherence) and what it means (its destination). A philosophy in turn provides the framework for more specific kinds of scholarship, such as the sciences, to look at the diversity of reality. The model illustrated here posits the immanent realm as the common experience for such scientific study, while at the same time showing why the transcendent “religious depth dimension” is so important. That is, we cannot locate the centre of reality without God’s revelation of its unity of origin and destination – which is Christ, the revelation of God as both transcendent and immanent. Without that special revelation, the human heart is inevitably drawn towards seeking explanatory unity in one or other aspect of created diversity – which leads to idolatry. This is what Dooyeweerd means by ‘secularisation’, and the dotted hearts in the diagram here represent some important idolatries of this kind that have shaped Western culture.

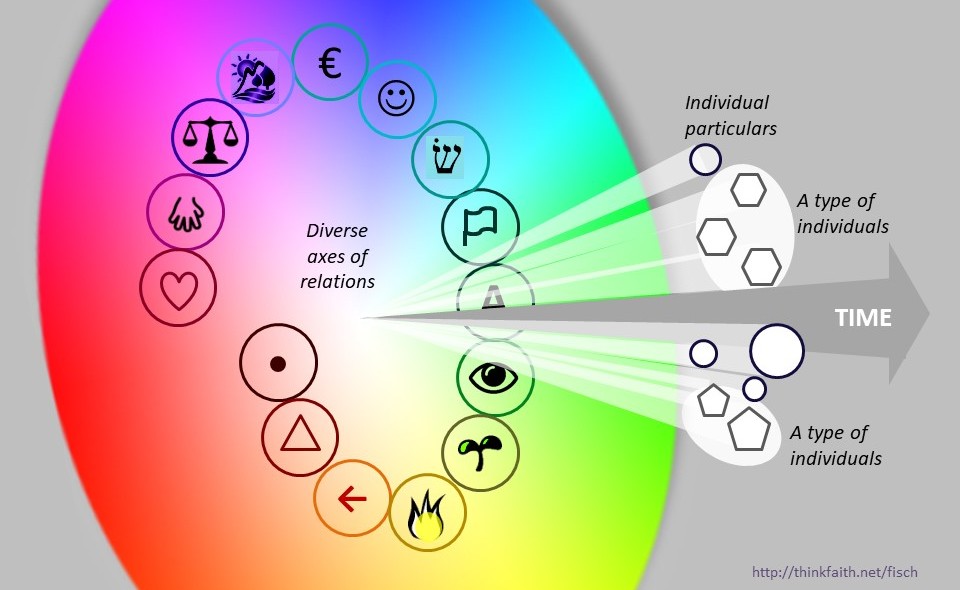

Individuals, Types and Relationships

As mentioned already, scientific thinking does not concern the uniqueness of things so much as classes, properties and behaviours that can be observed across multiple individuals or situations. In French, scientific knowing is generally savoir, not connaître, distinguishing knowing about generalities (or that something pertains) from knowing particulars (like people, pets and places). In English the distinction is simply between intransitive vs. transitive verb forms, but the contrast remains. It would be a strange question if I asked a zoologist, “How well do you know the alligator?” I’d probably be asking about a particular alligator – unless I were using the old-fashioned idiom whereby species are taken as particulars (echoes of platonic realism!). But my zoologist friend’s professional interest would be in knowing about alligators in general: how they live. Or turning to the Bible for a moment, we may note that while most of the canonical material is about particular people, places and event, the wisdom literature (e.g. Job, as magnificently explored by Tom McLeish) dwells extensively on generalities and might be seen as proto-scientific.

Science as abstraction

Many scientific fields have their origins in taxonomy: describing and classifying types of rocks and stars, species of organisms and diseases, personality types, family structures, etc. And thus the sciences proliferate concepts for types of particular things within a certain domain of interest. Developing sciences then take increasing interest in assessing temporal processes and interactive relationships: sedimentation, gravitation, reproduction, infection, development and geographical prevalence, for example – mostly using quantifiable variables. These characteristically scientific interests concern conceptual abstraction. And modally-specific abstraction is perhaps the best single characteristic of ‘science’.

For all the celebration of science as a source of empirical knowledge, the empirical basis of abstraction is rather obscure. How do we come to see that this truffle and that truffle are both truffles, or to classify rocks – despite the fact that every single specimen is unique? Biologists may fall back on the biological species concept – but this is more of an ideal than a useful tool. If we seek refuge in nominalism and pretend we just made up the types for convenience, then the taxonomic elements of our sciences lose their appeal. But just as problematic is the abstraction of variables relevant to scientific processes and relationships – like mass, temperature, lifespan, fecundity and relatedness. How do scientists form these concepts and then discover theoretical relationships and formulate laws (often mathematically-beautiful ones) – merely from experiencing unique particulars? It would seem that humans actually engage with the law-side of creation. We look in more detail at this under “A Model for Scientific Progress” below – but back to the diagram above.

The particular things we directly experience (the white shapes) provide specific data for scientific reasoning, and subjects for scientific prediction, but the abstract kinds (white patches) and diverse relations (the rainbow aura) are perceived in a different way. Hendrik Hart describes them as conditions and laws. As such, he says that they are real but do not exist; instead they ‘apply’ or ‘hold’. Turning again to the Bible (especially the Psalms), this also seems to be the sense in which God’s word is real without being a creature. And here lies a key reason why this framework has a particular claim to being Christian.

For now, lots of intriguing questions arise – e.g.:

- How do scientists actually relate data (particulars) to theory (abstract generalities)?

- Can a study of star constellations be called scientific? Or the discovery of a new planet, or of an underwater volcano?

- Does history count as a social science, or is it just about unique particulars?

- Can theology be the science of God? If not, is it the science of something else (like God’s revelatory actions)?

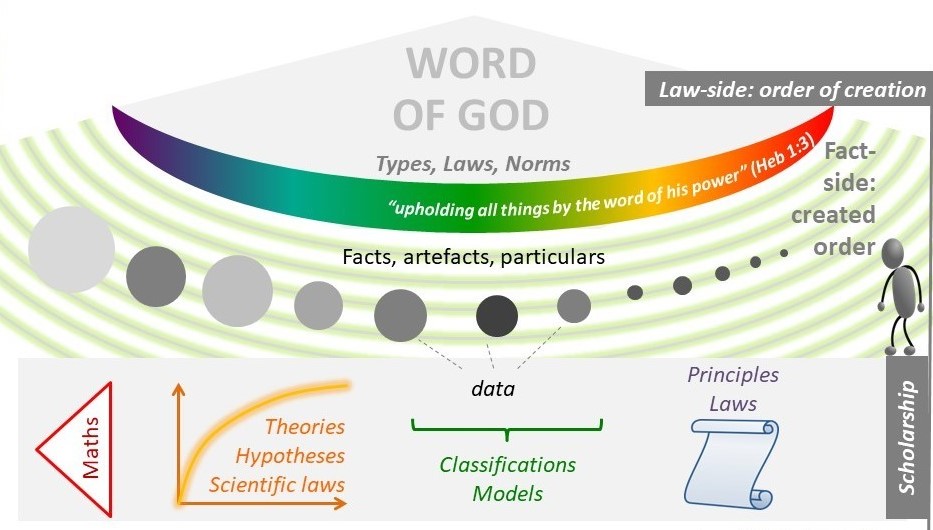

A Metaphysics for the Sciences

This diagram sketches how we create scholarly artefacts with reference to data. Data are part of the ‘fact-side’ [1] of the created order: the concrete entities, situations and phenomena that exist and that we can experience – all, like ourselves as human beings, subject to God’s creative word. That word (God’s word of power) has been likened [2] to a radio broadcast permeating the cosmos, to which every creature tunes in on some wavelength. The scientist attempts to describe the radio waves themselves, which are the specific laws, structures and types.

Scholarly artefacts (concepts, laws, models, etc) thus refer beyond the fact-side of reality to the law-side (top tier of the diagram). People don’t have to accept God’s revelation in the Scriptures and in Christ in order to probe the structure of creation, God’s ‘general revelation’. But we can see natural laws, types and norms as the refraction of God’s word into the diverse coherence of the order of creation, or the principles that structure the created order.

This definition of the sciences has important implications for how we relate scientific ideas to our daily Christian living and thinking. For example:

- The Bible generally refers to facts: specific events, relationships, and persons and their acts (including God’s self-revelation). Some regularities are of course described, such as God’s faithful covenantal behaviour towards creatures – but these are still facts, not scholarship. Arguably the Bible is no more a theological textbook than a scientific one.

- Scientific work does not produce simple ‘facts’ (these are its data) but ‘artefacts’: e.g. hypotheses, laws and theories. Hypotheses may refer to particulars (like the date of Jericho’s fall), but the term ‘facts’ is better reserved for beliefs founded on people’s direct experience of particulars (like that event as witnessed by Joshua).

- No-one has privileged access to the law-like refraction of God’s word of power. Scientific training, insofar as it conforms our minds to the structures of the created order, can help us perceive it – and increasingly as we submit to the diverse, meaningful interconnectedness of that order.

- Scientific knowledge is thus, in a sense, beliefs about the law-structure of the cosmos that are always subject to revision. They may still be highly reliable and – for all we know – approximately correct.

[1] ‘Facts’ in the sense of unique particular realities, not incontestable propositions in general. Reformational philosophers also call this the ‘subject-side’ of reality, because it comprises things that are subject to laws (which constitute the law-side of reality).

[2] by David Hanson, Faith-in-Scholarship advisor.

A Model for Scientific Progress

Christian thinkers have proposed a range of ideas about what science is, ranging from reading the book of God’s works and “thinking God’s thoughts after Him” to studying how the Universe runs itself if God doesn’t intervene. Views like these were expressed by early modern scientists (Galileo, Bacon, Newton and others) who were Christians of one sort or another, but they needn’t be the last word for a theistic perspective on science.

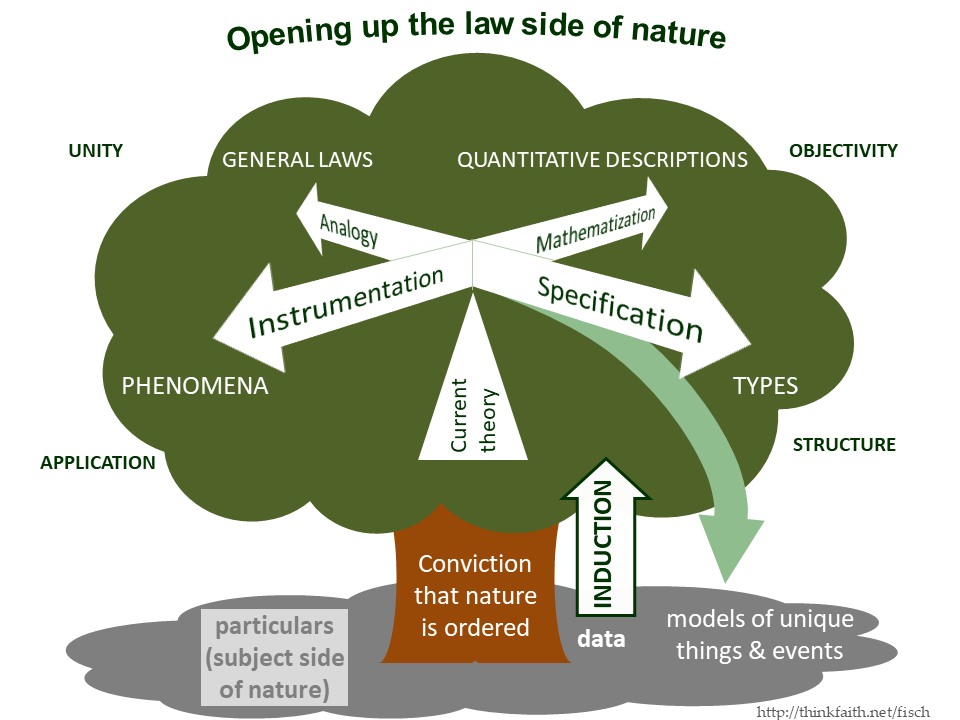

Ever since studying history of science as an undergraduate, I’ve been dissatisfied with the Enlightenment humanist motifs inherent in much of what passes for Christian thinking about the nature of science and scientific progress. By and large it’s assumed that there is a basic scientific method that results in an ever-more detailed, precise and unified description of the functioning of reality – which is the aim of science. The diagram here represents a model that’s less simplistic and arguably more realistic. It’s based on Dick Stafleu’s “theory of the opening process”, expounded in his works Theory and Experiment and Time and Again.

We start with a more nuanced definition of what science is. For Karl Popper and his followers, it’s all about dreaming up better hypotheses and testing them – but this arguably derives from a humanistic worldview where science advances by sheer creative genius (Popper says little about how scientists come up with successful hypotheses). For Stafleu, the aim of science concerns laws: “the opening up of the law side of nature”. “Law” is used in the broadest sense, for general relationships and patterns that hold in the world: gravitation, the existence of electrons, freezing points, food chains, etc, while “opening up” is a metaphor for discovery that emphasises the givenness of the created order alongside our freedom to describe it as best we can. It seems to evoke opening up a set of Russian dolls, or opening windows from one domain into another, and perhaps also creating unimagined new spaces, as when a house is opened up by removal of interior walls.

Progress on all fronts

The central point of Stafleu’s model is that scientific progress has multi-dimensional structure: our view is impoverished if we simply think of linear progress. I’ve tried to depict the elements of this model in the diagram above. The body of scientific understanding is represented here by a tree that can only be accessed when people are convinced that reality is law-abiding and ordered (the trunk). There are then three important distinctions:

- The tree of science (its law statements) must be distinguished from the ground of our experience of particular reality (subjects, or facts). For example, data arise from particular situations and entities at moments in space and time, and it’s by induction that we move towards general statements and models (up into the tree). Conversely, there are particular things and events, like the Solar System or the evolutionary history of a species, on which scientific understanding can subsequently be brought to bear (pale green arrow).

- Scientific progress has often come through putting numbers on things. ‘Mathematising‘ phenomena that are intrinsically physical, biotic, sensory, etc, is what Stafleu calls objectification (upper-right arrow): processes occurring among physical or biotic subjects are projected onto a numerical plane as objects on which measurements can be made. At the same time, very different kinds of scientific advances have also been made by applying new instruments to create novel phenomena (lower-left arrow) – as in the case of Galileo’s telescope, Boyle’s air-pump or Hooke’s microscope. Such phenomena may in turn be mathematised.

- Starting from a given body of theory about some aspect of reality, progress can be made on the one hand by recognising analogies that reveal general, unifying laws of nature – such as Newton’s first law of motion that recognises uniform motion as a simple kinetic reality, or the law of universal gravitation that recognises the spatial aspect of gravity (upper left arrow). On the other hand, progress can be made by describing things more and more precisely – like the structure of an atom or cell, or phylogenetic relationships among species – progressively specifying nature’s structure and types, and building more accurate models (lower right arrow).

Here I’ve only been able to give a superficial gloss of Stafleu’s model, for more explanation of which I can recommend Chapter 1 of Time and Again or Chapter 9 of Theory and Experiment. What I find inspiring about this view is its richness, capturing so much more of what goes on in scientific discovery than do typical accounts of scientific method. Some people find Reformational accounts like this to be baroque and implausibly complicated. But as a biologist who’s regularly amazed at the complexity of the created order, I find such a multifaceted model of science itself very plausible indeed.

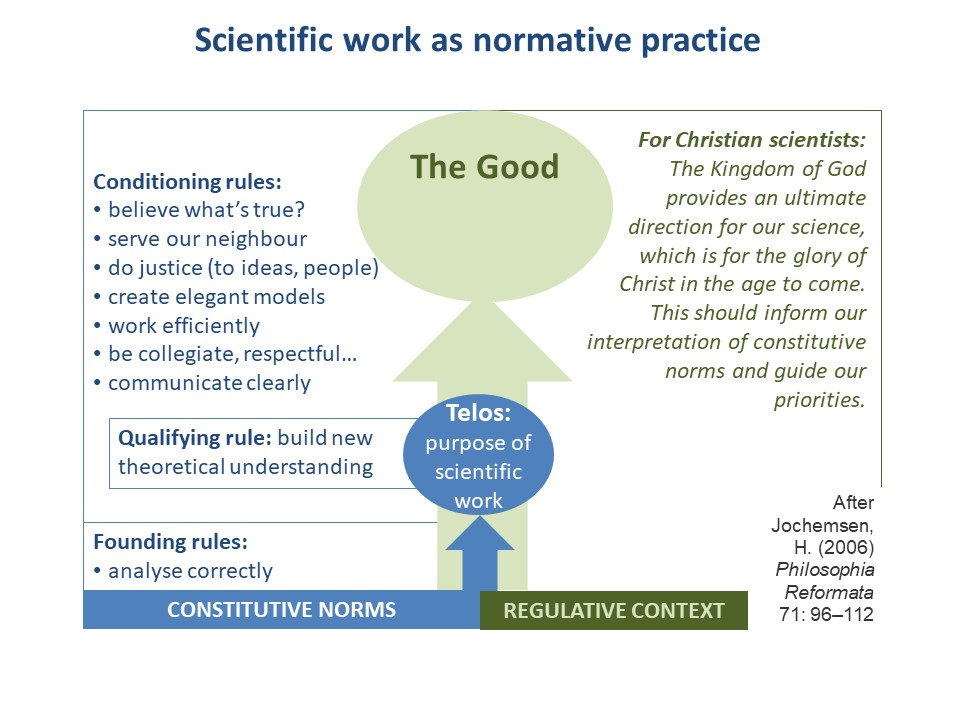

Norms and Ethics for Scientific Work

Norms are everywhere in science. A science education focuses on the constitutive norms: how to do science well. But it can be more effective if it also extends to touch on the telos of science: the context that makes sense of individual scientists’ behaviour. Each scientist’s view of ultimate good shapes what they actually do, feeding back into the norms.

Christian scientists can aim to build models, theories and applications that will have a place in Christ’s eternal kingdom [1].

[1] See, e.g., Revelation 21:24.

This is work in progress, so come back here for any new diagrams. Meanwhile, for a different kind of visual tour through the ideas and concepts of Church Scientific, try the animated Prezi of the 2018 workshops programme.