The “biological sciences” workshop at the Church Scientific began with short presentations by Clare O’Reilly and Stuart Egginton. Clare is a PhD student in history of science, and Stuart is Professor of Exercise Science, both at the University of Leeds.

Here you can see short overviews of the presentations they gave.

Christianity and science: a biologist’s view

Stuart pointed out a range of ways in which Christian a worldview is consonant with scientific work, and that flashpoints where conflict is sometimes evoked are often set up by holders of extreme views rather than arising as genuine problems.

Stuart’s slideshow can be viewed by clicking through the gallery below.

A biological controversy

Clare’s talk took us to a controversy about a controversy! Did Christians in Victorian Britain think that producing plant hybrids was wrong? And if not, why not?

To follow the presentation, scroll down through the slides and notes below.

I used to be a plant scientist but am now doing a PhD in history of botany.

This is a small bit of original historical research on plant breeding in the 19th century.

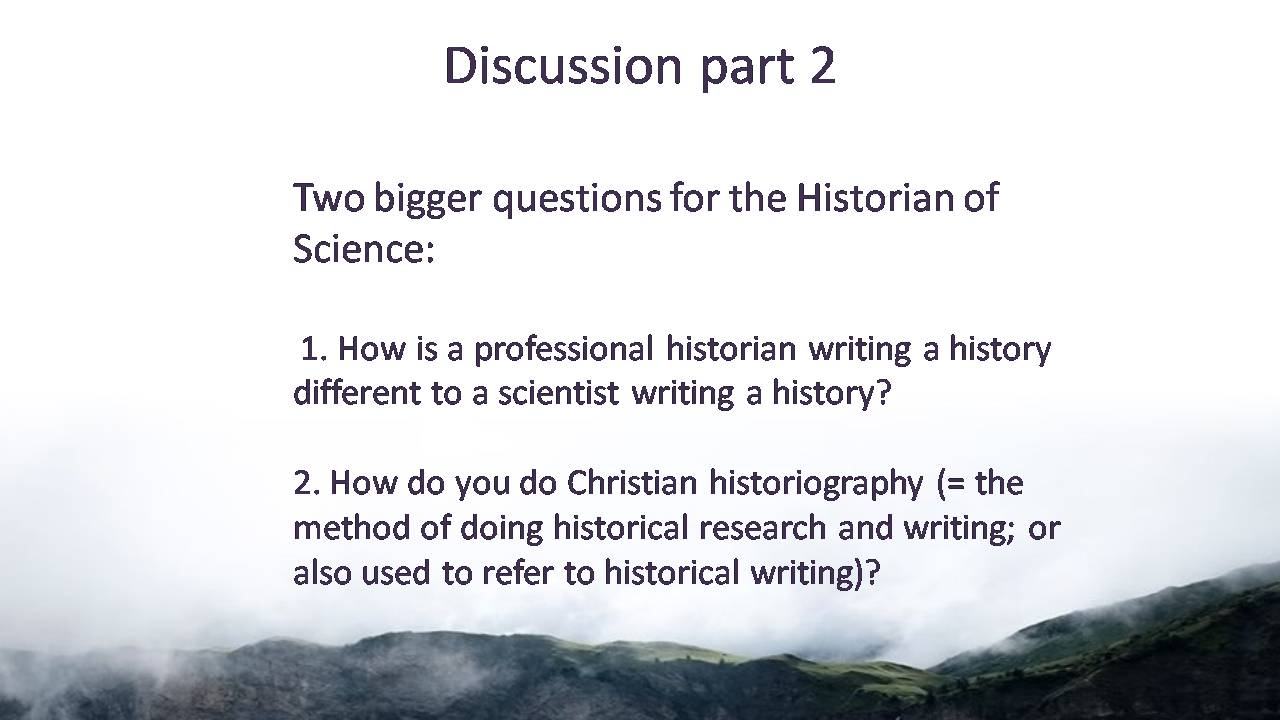

I also ask what sort of history writing can and should be done by Christians and how does it differ from history written by others?

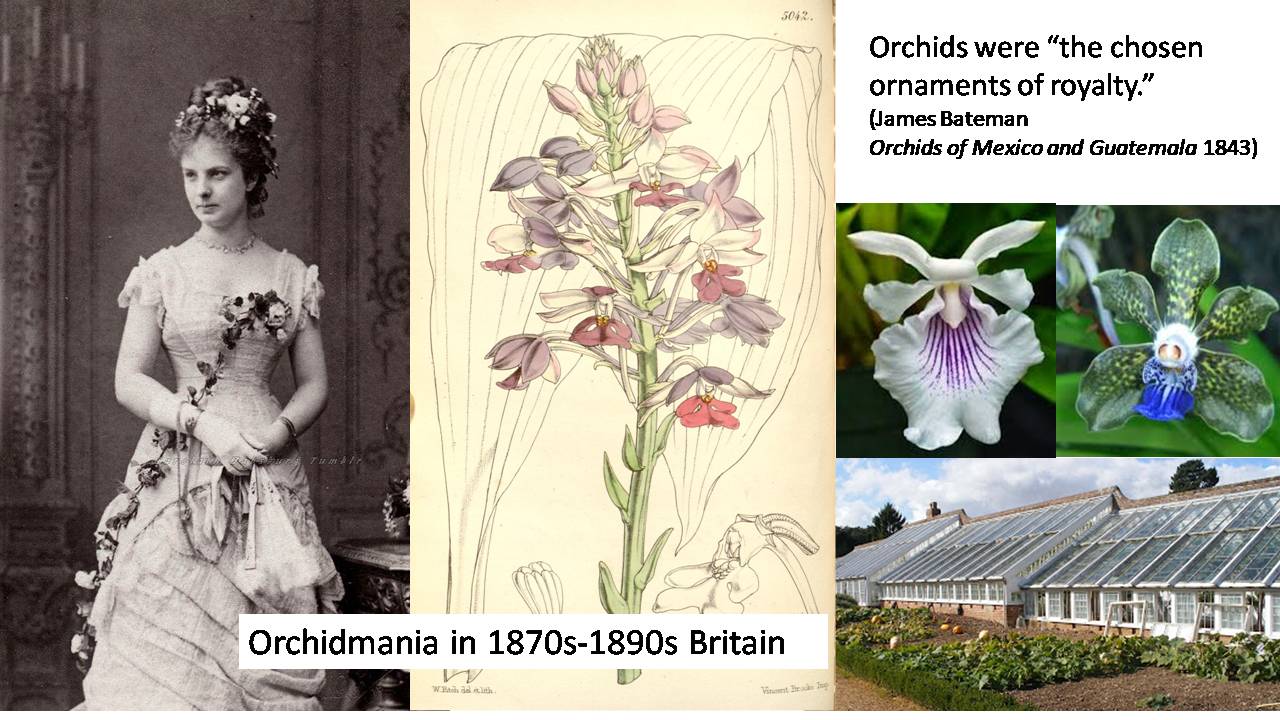

In 1850 in Britain, a glasshouse was *the* sign of social success. Every aspirational middle and upper-class household had to have a glasshouse and, preferably, a stove or hothouse with tropical orchids to go in it.

Orchids were “the chosen ornaments of royalty.” Women even decorated their dresses with orchids.

People would pay exorbitant sums for rare blooms. The highest price for a single orchid was 650 guineas (c. £298,000) at auction in 1870s.

Plant breeders responded to the orchidmania and demand for novel forms by cross-breeding.

The picture in the centre is the first ever artificially bred hybrid orchid, made in 1858.

Why were some botanists so hostile to hybrids?

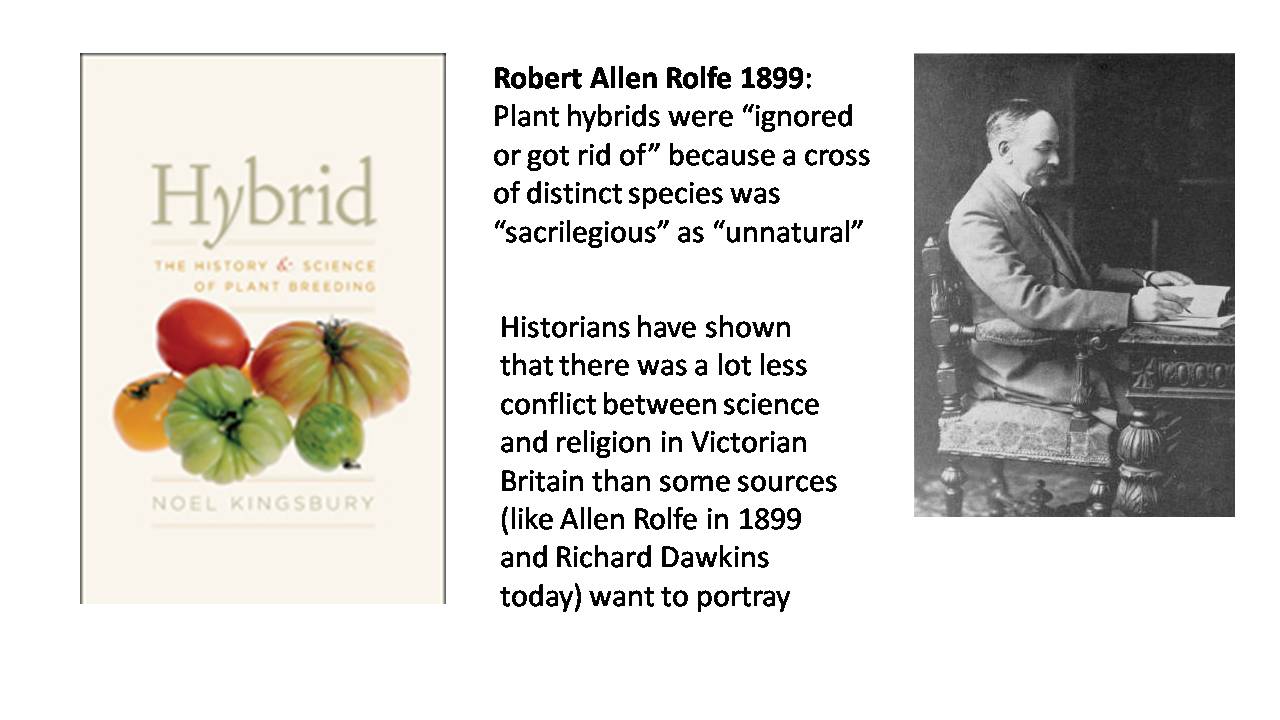

Robert Allen Rolfe wrote a history of hybridization in 1899 and stated that hybrids were “ignored or got rid of” because a cross of distinct species was “sacrilegious.”

In 2001, a gardening journalist, Noel Kingsbury, wrote a book on the history of plant breeding and was puzzled: he spent ages trawling through archives and old journals and couldn’t find any evidence that people were against hybridising for religious reasons. He concluded that he had just not done enough research.

Could it simply be that there is no evidence that Christians opposed plant hybridising because they didn’t?

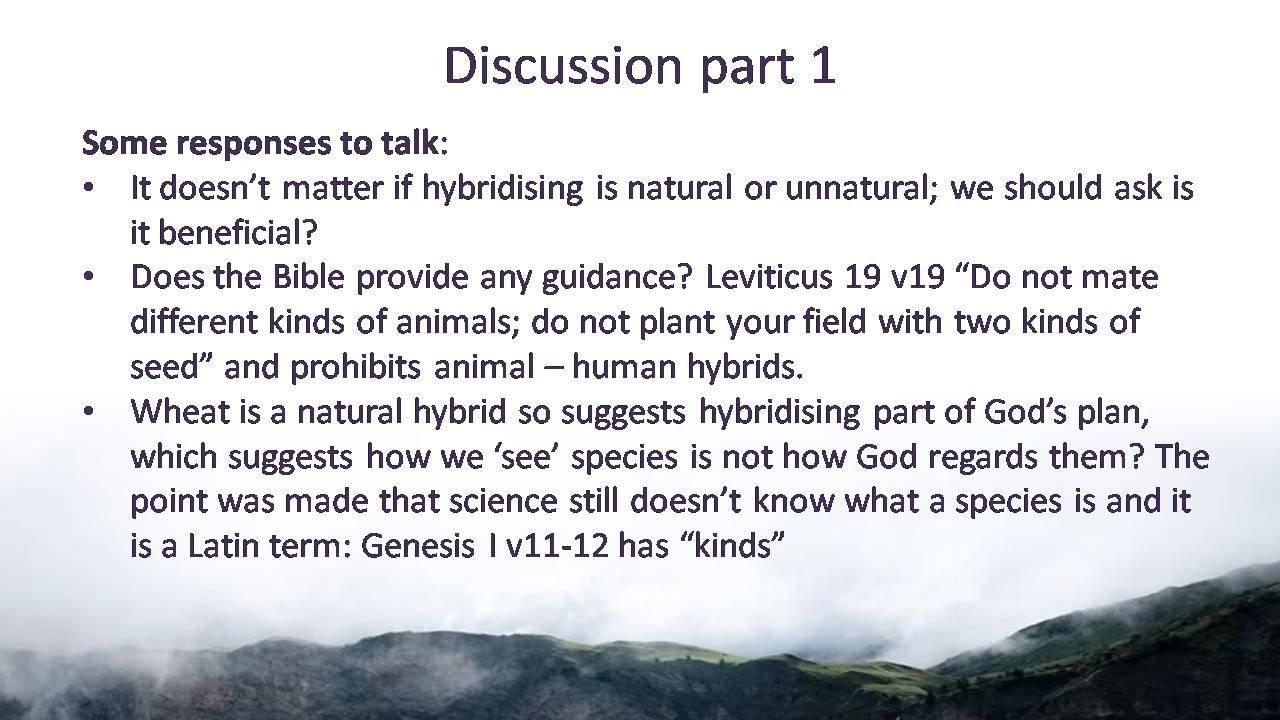

Rolfe made an assumption that their Christian faith meant they opposed hybrids because they regarded a plant hybrid as unnatural and wrong. In the mid 19th century before and after 1859 most Christians followed a non-literal interpretation of the Old Testament in order to reconcile scripture with science. Many Anglican vicars were cross-breeding and hybridising plants. Biblical statements about cross-breeding (Leviticus) were considered historical advice for survival in harsh conditions.

The modern journalist also back-shadowed today’s arguments about natural and artificial on to the 19th century – he was expecting people to be opposed to plant hybrids as unnatural in the way that people oppose GM crops today.

I think a Christian approach to the history of science takes religion seriously: it would ask the question, how did people’s beliefs influence their practices of science? But it also is aware that sources may impose religious motives where there were none.

These points were discussed after a longer version of this talk at the Church Scientific café evening in March 2017. Interestingly, some evangelical Christians in America are now using the argument made by plant breeder and vicar Rev. William Herbert, in 1837: that the diversity of species we see is not the result of transmutation (what the Victorians called evolution), but instead God created the genera, a few “kinds”, and then these interbred, hybridising to produce the diversity of species. Hybridization is being revisited as an alternative to evolution.

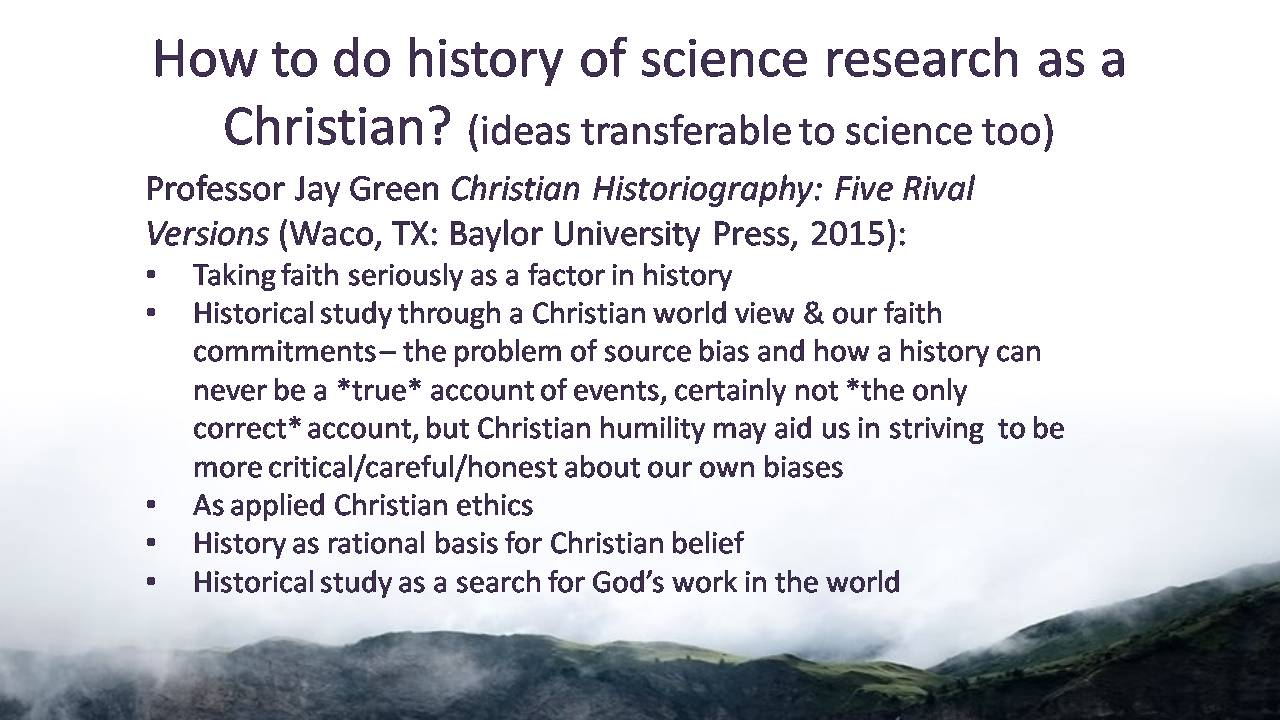

First two bullet points are highly regarded approaches but not straightforward.

1. How does a Christian scholar see differently? This view claims we do – more than Christian values applied to our research? – arrogant to say being a Christian means you do better research than non-Christian? In historiography there has been trend to do it from a certain perspective e.g. Marxist or feminist – but consensus now: that is impoverished history and best practice is to produce wider holistic histories.

2. Can faith make us free from political agendas?

3. Applied Christian ethics is problematic as it involves judging the past from today’s standpoint: while there are timeless truths in the Bible, how people interpret these inevitably involves their cultural context – being a Christian today is not the same as in the 19th century.

4. History as rational basis for Christianity – problem of looking for evidence to back Christians as a pivotal force for good; arguably reduces Christian scholarship to propaganda.

5.The last one is basically providentialist history. Professor Green is particularly against this approach.

While it is important to keep God central, there are two main problems:

- How does a human historian understand God’s purposes by studying events? Scripture repeatedly stresses we cannot and should not – e.g. historical events in scripture are unique revelatory events; Romans 11: God’s judgements are unsearchable; who has known the mind of the Lord?; Job…

- The big risk is that the historian aligns their own political interests in the course of history with God’s – produces a narrative that sees events as showing you have God on your side.